Tuesday, December 06, 2011

When kids used to go down to the Kennebec River to get Atlantic salmon for breakfast.

Citation: Boardman, Samuel L.: in Ninth Annual Report of the Secretary of the Maine Board of Agriculture. 1864. Augusta, Maine. Stevens & Sayward, Printers to the State. Subsequently published in the Maine Farmer, March 23, 1865.

At page 109:

"An aged woman, who formerly lived on the banks of the Kennebec in Vassalboro, and who, at that time, had a large family of children to support, once told me that, in spring and early summer, the fish from the river were a very essential aid to them -- that many times she has sent one of her boys down to the river early in the morning to catch a salmon for breakfast, with as much certainty that he would bring one home in season, as if she had sent him with the money to a city fish market, where she knew they were kept for sale."

How Maine's Sea-Run Fish were Dammed into Oblivion, 1864.

Citation: Boardman, Samuel L. 'Aquaeculture': in Ninth Annual Report of the Secretary of the Maine Board of Agriculture. 1864. Augusta, Maine. Stevens & Sayward, Printers to the State. Also pub. in Maine Farmer, March 23, 1865.

At p. 109-110:

"Everyone now knows that salmon, shad and alewives, and indeed all the other kinds of migratory fishes -- those that spend winters in the salt water, and come up out of the sea at certain periods, as if sent by a kind Providence, to spend the spring and summer in fresh water -- are now very scarce indeed, and in some streams totally extinct. Everyone knows, too, that many of the species of fishes which remain permanently in our fresh waters, have very much decreased in numbers, as well as in size and fatness. People say that this is a necessary consequence of the building of dams and mills, and filling the streams with obstructions of various kinds for the industrial pursuits of a civilized community. No doubt it is a consequence of these obstructions, but it not need be a necessary consequence. I hold that dams and mills might be constructed, and continued, and yet by a little concession on the part of dam and mill proprietors, and a more general diffusion of the knowledge of the natural history fishes, more intimate acquaintance with their peculiar habits, instincts, and wants of life, the mills might remain and the fish continue to perform their annual pilgrimage to and from their breeding haunts, if not in so great numbers as in former times, yet in such numbers as to afford a vast amount of provisions and even luxury to the communities which are now wholly deprived of them.

"I am also aware that this subject has been discussed over and over again -- that for years and years past, every session of our Legislature was thronged, and committees were worried and teased by mill owners on the one hand and fishermen on the other -- one demanding the privilege of building dams and mills without let or hindrance as to the fish, and the other pleading for some reserve, some fish-way, or some accommodation to the annual flow of the fish, which had been of such signal service to the support of the people on the banks and vicinity of the waters in question. I am also aware that our Legislators, actuated by a sincere desire to do justice to all parties, and to give equal rights to all, have, in most instance, made provisions in the several charters and private acts pertaining to mill owners, for the passage of fish at certain times and seasons, with a hope that, while it encouraged the establishment of mills and machinery, there would be also at the required times a safe and successful transit for the various species of fishes that required such passes as one of the indispensable requirements for the continuation of their existence. And we are all aware also that, either from ignorance of what habits of the fish demand, these ways have not always been properly constructed, or from selfishness in mill owners in not keeping them open at suitable times, these provisions in most cases failed, and the destruction of the fish is the inevitable result."

At p. 109-110:

"Everyone now knows that salmon, shad and alewives, and indeed all the other kinds of migratory fishes -- those that spend winters in the salt water, and come up out of the sea at certain periods, as if sent by a kind Providence, to spend the spring and summer in fresh water -- are now very scarce indeed, and in some streams totally extinct. Everyone knows, too, that many of the species of fishes which remain permanently in our fresh waters, have very much decreased in numbers, as well as in size and fatness. People say that this is a necessary consequence of the building of dams and mills, and filling the streams with obstructions of various kinds for the industrial pursuits of a civilized community. No doubt it is a consequence of these obstructions, but it not need be a necessary consequence. I hold that dams and mills might be constructed, and continued, and yet by a little concession on the part of dam and mill proprietors, and a more general diffusion of the knowledge of the natural history fishes, more intimate acquaintance with their peculiar habits, instincts, and wants of life, the mills might remain and the fish continue to perform their annual pilgrimage to and from their breeding haunts, if not in so great numbers as in former times, yet in such numbers as to afford a vast amount of provisions and even luxury to the communities which are now wholly deprived of them.

"I am also aware that this subject has been discussed over and over again -- that for years and years past, every session of our Legislature was thronged, and committees were worried and teased by mill owners on the one hand and fishermen on the other -- one demanding the privilege of building dams and mills without let or hindrance as to the fish, and the other pleading for some reserve, some fish-way, or some accommodation to the annual flow of the fish, which had been of such signal service to the support of the people on the banks and vicinity of the waters in question. I am also aware that our Legislators, actuated by a sincere desire to do justice to all parties, and to give equal rights to all, have, in most instance, made provisions in the several charters and private acts pertaining to mill owners, for the passage of fish at certain times and seasons, with a hope that, while it encouraged the establishment of mills and machinery, there would be also at the required times a safe and successful transit for the various species of fishes that required such passes as one of the indispensable requirements for the continuation of their existence. And we are all aware also that, either from ignorance of what habits of the fish demand, these ways have not always been properly constructed, or from selfishness in mill owners in not keeping them open at suitable times, these provisions in most cases failed, and the destruction of the fish is the inevitable result."

How Maine's Sea-Run Fish were Overfished to Oblivion

A few early to mid 1800s historic references I just came across illustrate how early and quickly the sea-run fish of Maine rivers were wiped out by over-fishing:

Citation: William Durkee Williamson. 1832. The History of the State of Maine. Vol. 1. Glazer, Masters & Co. Hallowell, Maine.

At p. 158, describing striped bass:

"The Bass is a large scale fish, variable in its size from 10 to 60 pounds. They are striped with black, have bright scales and horned backs, and are caught about the coasts. They ascend into the fresh water to cast their spawn, in May or June, being lean afterwards and fat in the autumn. In June 1807, there were taken at the mouth of the Kenduskeag, 7,000 of these fishes, which were of a large size -- a shoal, either pursued up the river by sharks, or ascended in prospect of their prey, or to cast their spawn."

Smelt at p. 160:

"They are caught in abundance, after March, in our rivers; 20 barrels of them have been taken at the mouth of the Kenduskeag at a sweep, and sometimes they are worth no more than half a dollar a bushel."

At footnote 3, same page: "On the 2d of May, 1794, at the mouth of the Kenduskeag (on the Penobscot) were taken at one draft 1,000 shad and 30 barrels of alewives."

----

Citation: Boardman, Samuel L. 'Aquaeculture': in Ninth Annual Report of the Secretary of the Maine Board of Agriculture. 1864. Augusta, Maine. Stevens & Sayward, Printers to the State. Also pub. in Maine Farmer, March 23, 1865.

At p. 117:

"Three years ago, in the month of May, in company with a friend, while passing by the lower lock of the Cumberland and Oxford Canal, in the city of Portland, our attention was drawn to the a crowd of men standing by the side of the lock, several of whom had long-handled nets, with which they were fishing, or rather dipping out fish from the water. On coming up, we saw that they were catching alewives in great numbers. It appeared that these fish, in their peregrinations along the coast, had been attracted by the fresh water of the canal, and instinctively entered it in order, as they supposed, to follow up to its source, (Sebago Lake,) but were brought to a standstill by the upper gate of the lock. The men engaged there then shut the lower gate, and commenced catching them. As soon as those of them that were confined in the lock were all caught, the men opened the lower gate again, and admitted a lot more of them, and thus a wholesale destruction of them went on. I supposed that some of them might possibly work their way up, when the several locks should be opened for the passage of boats, and thus Sebago made a breeding place for them, but on inquiry, am told that there are few or none seen there. Now it would be a very easy matter to stock that lake with young herrings (alewives) by proprietors of the canal forbidding any of them to be caught on certain days, and placing men along the route to let them go through the gates into the lake. Indeed, it seems that by renting the privilege of fishing for them on certain days, some considerable revenue might accrue to the company, while the production of the fish would again become a benefit to the section of country through with the canal passes. The same system might be adopted on many streams by having fish-ways or fish-locks, to aid their ascent, with much benefit to the country and no detriment to the mill interests."

_______

Citation: Twelfth Annual Report of the Maine Board of Agriculture, 1867. Stevens & Sayward, Printers to the State.

At page 90: "In Monmouth they [smelt] run into some very small rills that lead into Cochnewagon Pond, and are dipped out in considerable quantities. In May, 1867, after it was supposed they were all gone, a fresh run occurred, that yielded thirty barrels."

Citation: William Durkee Williamson. 1832. The History of the State of Maine. Vol. 1. Glazer, Masters & Co. Hallowell, Maine.

At p. 158, describing striped bass:

"The Bass is a large scale fish, variable in its size from 10 to 60 pounds. They are striped with black, have bright scales and horned backs, and are caught about the coasts. They ascend into the fresh water to cast their spawn, in May or June, being lean afterwards and fat in the autumn. In June 1807, there were taken at the mouth of the Kenduskeag, 7,000 of these fishes, which were of a large size -- a shoal, either pursued up the river by sharks, or ascended in prospect of their prey, or to cast their spawn."

Smelt at p. 160:

"They are caught in abundance, after March, in our rivers; 20 barrels of them have been taken at the mouth of the Kenduskeag at a sweep, and sometimes they are worth no more than half a dollar a bushel."

At footnote 3, same page: "On the 2d of May, 1794, at the mouth of the Kenduskeag (on the Penobscot) were taken at one draft 1,000 shad and 30 barrels of alewives."

----

Citation: Boardman, Samuel L. 'Aquaeculture': in Ninth Annual Report of the Secretary of the Maine Board of Agriculture. 1864. Augusta, Maine. Stevens & Sayward, Printers to the State. Also pub. in Maine Farmer, March 23, 1865.

At p. 117:

"Three years ago, in the month of May, in company with a friend, while passing by the lower lock of the Cumberland and Oxford Canal, in the city of Portland, our attention was drawn to the a crowd of men standing by the side of the lock, several of whom had long-handled nets, with which they were fishing, or rather dipping out fish from the water. On coming up, we saw that they were catching alewives in great numbers. It appeared that these fish, in their peregrinations along the coast, had been attracted by the fresh water of the canal, and instinctively entered it in order, as they supposed, to follow up to its source, (Sebago Lake,) but were brought to a standstill by the upper gate of the lock. The men engaged there then shut the lower gate, and commenced catching them. As soon as those of them that were confined in the lock were all caught, the men opened the lower gate again, and admitted a lot more of them, and thus a wholesale destruction of them went on. I supposed that some of them might possibly work their way up, when the several locks should be opened for the passage of boats, and thus Sebago made a breeding place for them, but on inquiry, am told that there are few or none seen there. Now it would be a very easy matter to stock that lake with young herrings (alewives) by proprietors of the canal forbidding any of them to be caught on certain days, and placing men along the route to let them go through the gates into the lake. Indeed, it seems that by renting the privilege of fishing for them on certain days, some considerable revenue might accrue to the company, while the production of the fish would again become a benefit to the section of country through with the canal passes. The same system might be adopted on many streams by having fish-ways or fish-locks, to aid their ascent, with much benefit to the country and no detriment to the mill interests."

_______

Citation: Twelfth Annual Report of the Maine Board of Agriculture, 1867. Stevens & Sayward, Printers to the State.

At page 90: "In Monmouth they [smelt] run into some very small rills that lead into Cochnewagon Pond, and are dipped out in considerable quantities. In May, 1867, after it was supposed they were all gone, a fresh run occurred, that yielded thirty barrels."

Thursday, July 07, 2011

Monday, July 04, 2011

Clay is Rusted Feldspar

My wife Lori asked me to explain to her pottery class in a fairly simple way what clay is, where it comes from, and how it got here. So here's an attempt at a non-technical explanation.

Clay is feldspar rusting. This is an analogy, but not that far from the actual process. We all know what happens if you buy a nice, shiny piece of cast iron from the hardware store and leave it outside in the sun and rain. It quickly rusts. If you leave it out long enough, it turns to almost all rust. So what is rust?

Rust is primarily the minerals limonite and goethite, created when iron combines with oxygen from the atmosphere and oxygen in water. We all know that iron things tend to rust faster when wet than when dry. Moisture hastens rusting.

Feldspar is not iron. Iron is one element, iron. Feldspar is a large family of minerals made from oxygen, silicon, aluminum, sodium, potassium and calcium. Feldspar does not form on the Earth's surface. It only forms miles beneath the Earth's surface, where solid rock is naturally in a semi-liquid, molasses-like state.

Feldspar is only released from its 'natural' home and to the Earth's surface either when it is forcibly ejected from a volcano as lava or when, after hundreds of millions of years, the 2-3 miles of solid rock above the feldspar is eroded away, leaving the feldspar nakedly exposed on the Earth's surface. This is usually in the form of granite, which is a rock made of feldspar and quartz and some mica.

To add another analogy, just like a piece of fine pottery on the edge of a shelf 'wants' to fall on the floor and smash, feldspar 'wants' to turn to clay when it is exposed to the Earth's surface. The agent for the pot on the shelf wanting to fall down and smash is gravity (in outer space, pottery does not break, it orbits). The agent for feldspar wanting to turn to clay is a bit more complex, but similar in design to iron rusting. In both, the agents are primarily air and water.

In the presence of air and water at the Earth's surface, the most natural and restive state for feldspar is to re-align its molecules into clay molecules. Clay is a mineral, just like quartz or feldspar. It has a very regular and ordered crystalline structure, like a diamond or a cube of salt. The three predominant clay minerals are kaolinite, illite and montmorillonite. With a scanning electron microscope you can get pictures of very nice, well formed, plate-like clay crystals growing right next to a crystal of feldspar.

Feldspar becomes clay by slowly bringing water into its crystal structure, like a sponge left in a puddle of water. This water becomes part of the very fabric of the feldspar; like how iron becomes part of your blood cells. The feldspar wants the water. It likes it. Which brings us back to rust.

What we call rust is the natural state of iron on the Earth's surface. Iron readily combines with oxygen to make rust. It wants to become rust. In fact, we have to do all kinds of crazy things to prevent iron from becoming rust. We coat it with oils, with paint (like Rust-Oleum) or galvanize it with zinc, all to keep the iron from contacting oxygen in the air and oxygen in water, sort of like teacher chaperones at a high school dance. Left to its own device, feldspar becomes clay because it wants to; that is its most stable and natural state on the Earth's surface. Like a thrown ball 'wants' to come back down, feldspar wants to become clay. Clay is rusted feldspar; and the actual chemical reactions are not that different.

In Maine, where I live, from 1880-1930 there was a flourishing industry where large feldspar deposits were quarried and mined for use as ceramic pottery glaze. This was feldspar that had not yet had time to weather into clay. It is still solid enough to make a house foundation. But if you crush into a fine enough powder, it works beautifully as a glaze ingredient. Most of the feldspar mined in Maine was shipped to pottery works in New Jersey as a basic glaze ingredient for everything from fine plateware to toilet bowls. It was an 'industrial mineral,' as the saying goes.

The only reason Maine does not have deposits of natural, 'primary' clay is because for the past million years Maine has been scoured by successive, mile high glaciers every 100,000 years or so, which like a steel plow on a snow-filled driveway, scraped away all the clay and softened rock right down to hard bedrock and dumped the residue in the Atlantic Ocean. In the U.S., you have to go south of the line of glaciers, ie. Kentucky or Tennessee, to find clay deposits still intact and near where they were first formed. What we in Maine call 'marine clay' is actually the finely ground-up residue from the glaciers' scraping and grinding that has partly altered into true clay minerals and is on its way to doing so, give another 10 million years. That said, it is still perfectly usable as a slip or a low-fire earthenware body. Be patient, Maine !!!

Clay is feldspar rusting. This is an analogy, but not that far from the actual process. We all know what happens if you buy a nice, shiny piece of cast iron from the hardware store and leave it outside in the sun and rain. It quickly rusts. If you leave it out long enough, it turns to almost all rust. So what is rust?

Rust is primarily the minerals limonite and goethite, created when iron combines with oxygen from the atmosphere and oxygen in water. We all know that iron things tend to rust faster when wet than when dry. Moisture hastens rusting.

Feldspar is not iron. Iron is one element, iron. Feldspar is a large family of minerals made from oxygen, silicon, aluminum, sodium, potassium and calcium. Feldspar does not form on the Earth's surface. It only forms miles beneath the Earth's surface, where solid rock is naturally in a semi-liquid, molasses-like state.

Feldspar is only released from its 'natural' home and to the Earth's surface either when it is forcibly ejected from a volcano as lava or when, after hundreds of millions of years, the 2-3 miles of solid rock above the feldspar is eroded away, leaving the feldspar nakedly exposed on the Earth's surface. This is usually in the form of granite, which is a rock made of feldspar and quartz and some mica.

To add another analogy, just like a piece of fine pottery on the edge of a shelf 'wants' to fall on the floor and smash, feldspar 'wants' to turn to clay when it is exposed to the Earth's surface. The agent for the pot on the shelf wanting to fall down and smash is gravity (in outer space, pottery does not break, it orbits). The agent for feldspar wanting to turn to clay is a bit more complex, but similar in design to iron rusting. In both, the agents are primarily air and water.

In the presence of air and water at the Earth's surface, the most natural and restive state for feldspar is to re-align its molecules into clay molecules. Clay is a mineral, just like quartz or feldspar. It has a very regular and ordered crystalline structure, like a diamond or a cube of salt. The three predominant clay minerals are kaolinite, illite and montmorillonite. With a scanning electron microscope you can get pictures of very nice, well formed, plate-like clay crystals growing right next to a crystal of feldspar.

Feldspar becomes clay by slowly bringing water into its crystal structure, like a sponge left in a puddle of water. This water becomes part of the very fabric of the feldspar; like how iron becomes part of your blood cells. The feldspar wants the water. It likes it. Which brings us back to rust.

What we call rust is the natural state of iron on the Earth's surface. Iron readily combines with oxygen to make rust. It wants to become rust. In fact, we have to do all kinds of crazy things to prevent iron from becoming rust. We coat it with oils, with paint (like Rust-Oleum) or galvanize it with zinc, all to keep the iron from contacting oxygen in the air and oxygen in water, sort of like teacher chaperones at a high school dance. Left to its own device, feldspar becomes clay because it wants to; that is its most stable and natural state on the Earth's surface. Like a thrown ball 'wants' to come back down, feldspar wants to become clay. Clay is rusted feldspar; and the actual chemical reactions are not that different.

In Maine, where I live, from 1880-1930 there was a flourishing industry where large feldspar deposits were quarried and mined for use as ceramic pottery glaze. This was feldspar that had not yet had time to weather into clay. It is still solid enough to make a house foundation. But if you crush into a fine enough powder, it works beautifully as a glaze ingredient. Most of the feldspar mined in Maine was shipped to pottery works in New Jersey as a basic glaze ingredient for everything from fine plateware to toilet bowls. It was an 'industrial mineral,' as the saying goes.

The only reason Maine does not have deposits of natural, 'primary' clay is because for the past million years Maine has been scoured by successive, mile high glaciers every 100,000 years or so, which like a steel plow on a snow-filled driveway, scraped away all the clay and softened rock right down to hard bedrock and dumped the residue in the Atlantic Ocean. In the U.S., you have to go south of the line of glaciers, ie. Kentucky or Tennessee, to find clay deposits still intact and near where they were first formed. What we in Maine call 'marine clay' is actually the finely ground-up residue from the glaciers' scraping and grinding that has partly altered into true clay minerals and is on its way to doing so, give another 10 million years. That said, it is still perfectly usable as a slip or a low-fire earthenware body. Be patient, Maine !!!

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

Sunday, June 19, 2011

Fathers Day, Part I

Central Nebraska, 35,000 feet, 2 p.m., June 15, 2011.

Central Nebraska, 35,000 feet, 2 p.m., June 15, 2011.Fathers Day

We live on stolen land

But what of it.

It was the Indians' land

So we told them to shove it.

Now they exist in our minds

Like little figurines

On the mantel or in

some magazine.

Some folks are surprised

when a fox is in their yard

Forgetting it was first

the foxes' yard.

Things you ignore

Don't go away.

Because you don't care

if they go or stay.

No country cheers

that it's number two.

The sky doesn't cry

because it's blue.

It can't have happened both ways

if we want it to.

A lie becomes true

if enough believe it.

A child stays pure

until you deceive it.

Then the kid starts asking why.

It's okay for you but

not for me to lie.

You'll learn son sometimes

It's what it takes

to get by.

Tuesday, May 24, 2011

The Great Goddards Ledge Rose Quartz Conspiracy Hoax

Philip Morrill et al. (1958) described Goddards Ledge near Rumford Center, Maine as a rose quartz locality, found while the pegmatite was worked for ceramic feldspar in the WWII era.

So in 1993 I tried to find it. It's a nasty traverse, pretty steep, up the side of a mountain, unmarked, no trails and 'intermittently' posted. But what the hell. Plus it's raining (keeps the black flies and mosquitoes down). Up and away we go.

Bonanza !!! I found an old feldspar working littered with giant shards of glass quartz way up the mountain, under lots of mud and leaves. This must be it. Light going fast in the rain. It's all rose quartz. Unbelievable! Nobody has been here for decades. It's all mine !!!

Get home at 10 p.m. totally soaked in mud, get up, go to work, next day take out all the 'finds' and cover the kitchen floor of the apartment with them. Yes !!! Sun comes out next day. All the 'rose quartz' is amazingly clear and devoid of any pink coloration.

My landlord, Yvon Doyon, comes by for the rent. The whole house and deck are covered with pieces of non-rosy quartz. We have to step around them as I write him the rent check. He gives me a quizzical look. It's a tenement. Lots of 'not-normal' people live here, and I get the feeling Yvon has officially put me in that category.

I've been hoodwinked. Shamboozled. Schlamottled. Diabolicized. It's all NON rose quartz !!! How could this be?

I think it was becuz I was a wee bit too 'eager,' or as Jim Mann would say, 'rock warped.'

Actually, a dozen or so of the pieces are true rose quartz. The rest are so faintly tinted it would have taken rose quartz tinted glasses to see it. And apparently I was wearing coke bottles of that stuff when I was at Goddards Ledge. Oops.

But it gets worse. Much worse. The next spring I brought my girlfriend to Goddards Ledge as the 'first stop' on a Memorial Day camping vacation; and we both climbed the 800 foot nasty incline up to the 'quarry.' But we didn't find it. I followed the wrong ravine. Since there are no trails, it's a bit complicated. And every mosquito and black fly in Oxford County had our number. So we ran back down the mountain to the car, totally sweaty, hungry, disgusted and bug-bitten.

Except I could not find the car keys. They were somewhere 'up there' on the mountain. I had put them in my backpack (for 'safe keeping') and forgot to zip the pocket shut. So they could be anywhere between us and the non-Goddards Ledge quarry. Under the leaves. In between two rocks. Anywhere. And it was getting dark. Smooth move, Doug.

So back up the mountain and about halfway up I saw a glint. The keys !!! Really? The keys !!!

They had fallen out of my pack when I was skidding up or down a glacial erratic. God must have had mercy on me that day.

So some of the rose quartz at Goddard's Ledge in Rumford is genuine, if you don't get too over enthusiastic. And when fashioned en cabochon it does display 6, 8 and 12-star asterism, as Phil Morrill said in 1958.

But keep an extra set of keys under the car wheel. Just in case.

Monday, May 23, 2011

Getting Lost at North Twin Mountain, Rumford, Maine

North Twin Mountain is just a few miles to the north of Black Mountain near the Rumford/Andover line in western Maine, south of Maine Route 120.

Swains Notch is a split in the mountain chain, marked by a pond, where Phillip Morrill et al. (1958) described large quartz crystals in the 'dirt.' North and South Twin Mountains are historically documented as having unmined beryl pegmatite deposits on their shoulders.

In 1998 on a very rainy June day I got antsy around the house and drove 50 miles to 'attack' Swains Notch and North Twin Mountains and force them to divulge their secrets. What a mistake.

First, it was pouring out. Intermittently, but still pouring 15 minutes of each hour.

Second, I had not even a good USGS map to direct me; just the old Phillip Morrill quads from the Winthrop Mineral Shop.

Third, I had no idea where I was going, except to the end of 'Swains Notch Road' off the road leading to the Black Mountain quarry.

But what the hey. So I got out, shouldered pack, hammer and went uphill. Uphill seemed a good direction to go.

After about an hour of steep climbing, in intermittent yet pouring rain, I did find some unmined, glacially scoured pegmatite outcrops on the southern shoulder of North Twin Mountain. And rough but large beryl crystals were exposed in the pegmatite, if you ripped giant carpets of moss off them and coated yourself in mud. But hey. Edmund Bailey did it at Black Mountain in 1880. But maybe not in the pouring rain.

So I've climbed 1,000 feet, am totally sweaty and totally soaking wet and it is pouring out, did see some in situ beryl but its getting toward 3 or so, not that I have a watch. It just seems 3 or so. Better get off the mountain. Start following logging roads.

But they seem to be heading in endless zigzags. There is no 'down'; just a down followed by an 'up.' Where am I? I have no clue.

On a clear day I could climb a tree and get my bearings from Black Mountain, or any high spot, I know the terrain and landmarks fairly well. But it's pouring and foggy. Visibility is about 300 feet and no sign of it lifting.

I'm totally soaked now, 4 layers of clothes, it's pouring and I'm watching a ruffed grouse who is not so worried as myself. I know from my mental map (no compass ! idiot) that if I walk off the east side of the mountain I will not hit a road for about 5 miles, the Isthmus Road and it will be long past dusk. But I also know that my car is only about 1.5 miles away at most -- if I walk in the right direction toward it. And I have no idea and the logging roads are all doing curlicues and cul de sacs.

But then, in a birch grove, near a brook, a breeze ... a smell ... coming from downhill ... badly cooked cabbage and clam flat gas! Rumford. The smell is my compass!

There was a while I was a bit scared because I had never been so thoroughly lost before. But like a monkey with a typewriter I randomly moved toward the door and downhill and took a correct turn and saw Swains Pond, which I had never seen before, but I knew it was the right way. And the rain started to let up. It was just kind of misty when I popped out of the road at the end of the pond and after another half hour found the car.

It's quite a beautiful place.

Swains Notch is a split in the mountain chain, marked by a pond, where Phillip Morrill et al. (1958) described large quartz crystals in the 'dirt.' North and South Twin Mountains are historically documented as having unmined beryl pegmatite deposits on their shoulders.

In 1998 on a very rainy June day I got antsy around the house and drove 50 miles to 'attack' Swains Notch and North Twin Mountains and force them to divulge their secrets. What a mistake.

First, it was pouring out. Intermittently, but still pouring 15 minutes of each hour.

Second, I had not even a good USGS map to direct me; just the old Phillip Morrill quads from the Winthrop Mineral Shop.

Third, I had no idea where I was going, except to the end of 'Swains Notch Road' off the road leading to the Black Mountain quarry.

But what the hey. So I got out, shouldered pack, hammer and went uphill. Uphill seemed a good direction to go.

After about an hour of steep climbing, in intermittent yet pouring rain, I did find some unmined, glacially scoured pegmatite outcrops on the southern shoulder of North Twin Mountain. And rough but large beryl crystals were exposed in the pegmatite, if you ripped giant carpets of moss off them and coated yourself in mud. But hey. Edmund Bailey did it at Black Mountain in 1880. But maybe not in the pouring rain.

So I've climbed 1,000 feet, am totally sweaty and totally soaking wet and it is pouring out, did see some in situ beryl but its getting toward 3 or so, not that I have a watch. It just seems 3 or so. Better get off the mountain. Start following logging roads.

But they seem to be heading in endless zigzags. There is no 'down'; just a down followed by an 'up.' Where am I? I have no clue.

On a clear day I could climb a tree and get my bearings from Black Mountain, or any high spot, I know the terrain and landmarks fairly well. But it's pouring and foggy. Visibility is about 300 feet and no sign of it lifting.

I'm totally soaked now, 4 layers of clothes, it's pouring and I'm watching a ruffed grouse who is not so worried as myself. I know from my mental map (no compass ! idiot) that if I walk off the east side of the mountain I will not hit a road for about 5 miles, the Isthmus Road and it will be long past dusk. But I also know that my car is only about 1.5 miles away at most -- if I walk in the right direction toward it. And I have no idea and the logging roads are all doing curlicues and cul de sacs.

But then, in a birch grove, near a brook, a breeze ... a smell ... coming from downhill ... badly cooked cabbage and clam flat gas! Rumford. The smell is my compass!

There was a while I was a bit scared because I had never been so thoroughly lost before. But like a monkey with a typewriter I randomly moved toward the door and downhill and took a correct turn and saw Swains Pond, which I had never seen before, but I knew it was the right way. And the rain started to let up. It was just kind of misty when I popped out of the road at the end of the pond and after another half hour found the car.

It's quite a beautiful place.

Friday, March 11, 2011

How not to solder a padlock in the woods at midnight

Since my one attempt at teenage vandalism did not come close to succeeding, I can tell the story.

When I was in eighth grade, the big chunk of woods behind our house was purchased and subdivided for development into what are now called McMansions. Because the land is quite ledgy and rocky with Dedham granodiorite, the first two operations consisted of cutting down most of the trees and then dynamiting the ledges and hauling the boulders off the shattered land.

This did not sit well with me, but as a 15-year-old with $10 in my savings account I was quite helpless to stop it. The developers had all their legal permits.

The dirt road to the development was quite a ways in the woods and blocked by large metal posts driven into the ground and secured with ametal chain and a padlock the size of a softball.

One day after school I decided to solder the keyhole of the padlock that held the chain in place across the dirt road. That way the trucks couldn't get in and cut and dynamite any more trees and ledges down.

This plan would take cunning and stealth and certain pieces of equipment: a Bernzomatic blow torch and a roll of solder from the cellar. It would also require sneaking out of the house at night after my mother went to bed. It would also require a Hogan's Heroes type of disguise, which in this case was all the dark stuff I had in my bureau and a navy blue ski mask, even though it was summer.

Fully equipped at about 11 p.m. I snuck out of the house with ski mask, matches, torch and solder and hiked through the woods to the construction site and tried to find my way down the little, circuitous deer paths I chose so as not to be seen beneath a street light. Once I got to the chain and lock I discovered I knew nothing about how to solder, particularly the part about heating the lock as well as the solder, and I didn't bring any flux. So the solder kept beading up and rolling off the padlock didn't plug up the keyhole, which my plan required.

After a couple minutes I heard voices and leaves rustling in the woods and froze in a cold sweat with visions of the fluorescent lights of the Easton Police Station and the inevitable call home to mom that I had been arrested, was in the pokey and needed bail money to get out. As the voices got closer, I panicked and bolted as fast as I could in the opposite direction: deeper into the woods toward Stoughton. I fell a few times, banged my knees and head on rocks and trees, scraped my face on saplings but just got up and tried to run even faster. I was scared but also astonished. How could I so easily get discovered and caught?

There were yells and screams of "Someone's up there in the woods," and it sounded like half a dozen people were following me. By their footfalls and voices I could tell were spreading out to cut off my routes of escape and trying to flank me from the sides to cut off any alternate routes. So I ran faster, zigzagged like a tailback and tried to throw them off my intended path, which I didn't know.

They were gaining on me. Who were they? Did the developer hire Green Beret squads to camp out and watch over their stuff at night just to catch people like me who didn't know how to solder?

Finally, like a deer in a deer drive, or a rabbit chased by a wolf pack, I zagged when I should have zigged and got cornered and tackled in the leaves and rocks. The man who knocked me down pinned me on the shoulders. He was much bigger than me. I couldn't wriggle away or see him. "I've got him," he yelled and the rest of the group converged. "What's this," one said grabbing my hand, "It's a blowtorch."

I still had the ski mask on. The group converged over me with clenched fists and wild screams about 'let's kill him.' At this point I thought my face would probably not have recognizable features within a few minutes and waited to hear what your own bones sound like when they crack on a warm mosquitoey night. I thought I was going to die.

"Pull his mask off," they yelled. The lead guy ripped the ski mask off my head. Then they all said in a puzzled voice: "Drugless?" It was my schoolmates. "What the hell are you doing out here?"

I told them my story and they told me theirs. I was trying to solder a padlock in the middle of the night. They had all taken LSD and had been running around in the woods high as kites since it got dark.

"We came this close to killing you, you idiot." They said.

So the soldering the padlock idea didn't work out.

When I was in eighth grade, the big chunk of woods behind our house was purchased and subdivided for development into what are now called McMansions. Because the land is quite ledgy and rocky with Dedham granodiorite, the first two operations consisted of cutting down most of the trees and then dynamiting the ledges and hauling the boulders off the shattered land.

This did not sit well with me, but as a 15-year-old with $10 in my savings account I was quite helpless to stop it. The developers had all their legal permits.

The dirt road to the development was quite a ways in the woods and blocked by large metal posts driven into the ground and secured with ametal chain and a padlock the size of a softball.

One day after school I decided to solder the keyhole of the padlock that held the chain in place across the dirt road. That way the trucks couldn't get in and cut and dynamite any more trees and ledges down.

This plan would take cunning and stealth and certain pieces of equipment: a Bernzomatic blow torch and a roll of solder from the cellar. It would also require sneaking out of the house at night after my mother went to bed. It would also require a Hogan's Heroes type of disguise, which in this case was all the dark stuff I had in my bureau and a navy blue ski mask, even though it was summer.

Fully equipped at about 11 p.m. I snuck out of the house with ski mask, matches, torch and solder and hiked through the woods to the construction site and tried to find my way down the little, circuitous deer paths I chose so as not to be seen beneath a street light. Once I got to the chain and lock I discovered I knew nothing about how to solder, particularly the part about heating the lock as well as the solder, and I didn't bring any flux. So the solder kept beading up and rolling off the padlock didn't plug up the keyhole, which my plan required.

After a couple minutes I heard voices and leaves rustling in the woods and froze in a cold sweat with visions of the fluorescent lights of the Easton Police Station and the inevitable call home to mom that I had been arrested, was in the pokey and needed bail money to get out. As the voices got closer, I panicked and bolted as fast as I could in the opposite direction: deeper into the woods toward Stoughton. I fell a few times, banged my knees and head on rocks and trees, scraped my face on saplings but just got up and tried to run even faster. I was scared but also astonished. How could I so easily get discovered and caught?

There were yells and screams of "Someone's up there in the woods," and it sounded like half a dozen people were following me. By their footfalls and voices I could tell were spreading out to cut off my routes of escape and trying to flank me from the sides to cut off any alternate routes. So I ran faster, zigzagged like a tailback and tried to throw them off my intended path, which I didn't know.

They were gaining on me. Who were they? Did the developer hire Green Beret squads to camp out and watch over their stuff at night just to catch people like me who didn't know how to solder?

Finally, like a deer in a deer drive, or a rabbit chased by a wolf pack, I zagged when I should have zigged and got cornered and tackled in the leaves and rocks. The man who knocked me down pinned me on the shoulders. He was much bigger than me. I couldn't wriggle away or see him. "I've got him," he yelled and the rest of the group converged. "What's this," one said grabbing my hand, "It's a blowtorch."

I still had the ski mask on. The group converged over me with clenched fists and wild screams about 'let's kill him.' At this point I thought my face would probably not have recognizable features within a few minutes and waited to hear what your own bones sound like when they crack on a warm mosquitoey night. I thought I was going to die.

"Pull his mask off," they yelled. The lead guy ripped the ski mask off my head. Then they all said in a puzzled voice: "Drugless?" It was my schoolmates. "What the hell are you doing out here?"

I told them my story and they told me theirs. I was trying to solder a padlock in the middle of the night. They had all taken LSD and had been running around in the woods high as kites since it got dark.

"We came this close to killing you, you idiot." They said.

So the soldering the padlock idea didn't work out.

Wednesday, February 16, 2011

The Frates Dairy Milk Bottle, Raynham, Mass.

This is a fairly recent picture of the Frates Dairy Milk Bottle on Route 138 in Raynham, Mass. The milk bottle was going to be torn down a few years ago but thankfully some folks decided not to.

As a kid, it made perfect sense to stop and get an ice cream cone at a 60 foot high milk bottle.

Thanks, Frates Dairy.

Thursday, February 03, 2011

Some Background on our Maine Atlantic Salmon Lawsuit

Kennebec River Atlantic salmon, October 1996.

The following (written in op/ed-ese) for the Waterville, Maine Morning Sentinel quickly scopes the salient issues:

---

Breaking the Law is Different from Obeying the Law

By Douglas Watts

Augusta, Maine

Public documents going back 20 years show that hydroelectric dam owners on the Kennebec River have been aware that fish are sucked into their turbines and are killed and maimed. This happens because the intakes of the turbines are open and unscreened, like a window fan with no protective mesh.

Atlantic salmon are killed at hydroelectric dams by the same mechanism as shown above for American eels.

Atlantic salmon are killed at hydroelectric dams by the same mechanism as shown above for American eels.In June 2009 the few dozen remaining Atlantic salmon in the Kennebec were declared an endangered species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. It is a federal crime to kill a Kennebec River Atlantic salmon. If you or I did it, we would go to jail.

Kennebec dam owners continue to leave their turbines open and unscreened and allow Atlantic salmon to swim through them, leading to their death.

Because these dam owners have failed to take prompt action to protect the few Atlantic salmon left in the Kennebec, myself and Friends of Merrymeeting Bay and Environment Maine are suing these dam owners in federal court to stop this killing.

Putting in the turbine screens will cost the dam owners a minuscule fraction of their annual profits. Turbine screening has been done now for half a decade at the Benton Falls Dam in Benton and the American Tissue Dam in Gardiner with no effect on their ability to generate electricity.

The Kennebec River is owned by us; not out-of-state dam owners. Using a public river for private gain is a privilege, not a right, and with it comes a responsibility to not interfere with our rights to the river and our right to expect that all laws will be obeyed and endangered species will not be harmed or killed or go extinct. This is why we pass laws.

News item, Kennebec Journal, July 1880.

Hey !!! A big business law paper covered our Maine Atlantic Salmon lawsuit.

This piece is by subscription only, but cuz I was sent a copy by a subscriber and it's about me, I am going to let you read it:

----

Green Groups Sue Maine Dam Operators Over Salmon

By Bibeka Shrestha

Law360, New York (February 1, 2011) -- Two conservation groups have sued NextEra Energy Resources Inc. and other hydroelectric dam operators on the Kennebec and Androscoggin rivers in Maine, accusing them of harming the endangered Atlantic salmon population by allowing the fish to pass through turbines.

Friends of Merrymeeting Bay and Environment Maine filed four complaints on Monday against NextEra, Brookfield Renewable Power Inc., Topsham Hydro Partners Limited Partnership, Miller Hydro Group, Merimil Limited Partnership and several affiliates in the U.S. District Court for the District of Maine, alleging violations of the Endangered Species Act and the Clean Water Act.

The lawsuits target the owners and operators of four dams on the Kennebec River and three dams on the Androscoggin River, alleging these dams are killing or injuring migrating salmon that try to pass through spinning turbine blades, and are otherwise impeding the salmon's ability to travel upstream and downstream on the rivers.

The dam operators have violated the Endangered Species Act by preventing Atlantic salmon from reaching a significant amount of spawning and rearing habitats and significantly impairing the salmon population's essential behavior patterns, according to the complaint.

Merimil, NextEra, Brookfield and their affiliates are also violating the Clean Water Act by not conducting a required study to prove that allowing downstream-migrating adult salmon to pass through their dams' turbines is safe, the complaint said.

These companies are allegedly violating water quality certifications, which require them to conduct site-specific quantitative studies in consultation with the the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or the National Marine Fisheries Service to show that passage through the turbines does not result in significant injury or death.

Atlantic salmon were officially designated as endangered under the Endangered Species Act in June 2009, the same month the NMFS designated the Kennebec and Androscoggin rivers as critical habitats, according to the complaint.

The rivers, which share a common estuary at Merrymeeting Bay, historically enjoyed the largest Atlantic salmon runs in the country, estimated at more than 100,000 adults annually, according to the groups.

In 2010, however, 10 adult salmon returned to the Androscoggin and five adult salmon returned to the Kennebec, the groups said.

“These dams are pushing an iconic Maine fish to the brink of extinction," said Emily Figdor, director of Environment Maine, in a statement Tuesday. "With the number of Atlantic salmon perilously low, the need for action to protect the fish and their habitat is urgent."

The groups are asking the court to order the dam owners and operators to conduct a biological assessment to determine whether their actions are adversely affecting the salmon population.

They also hope to block the dam owners and operators from allowing salmon to swim through operating turbines unless they receive authorization through an incidental take permit or incidental take statement, which would require them to minimize and mitigate the impacts of harming the endangered fish to the "maximum extent possible," the complaint said.

The groups claim the dam owners can implement simple measures, such as installing effective devices to divert salmon from turbines and stopping the turbines during salmon migration season.

"The salmon population is nearly extinct, and the dam owners and operators need to take immediate steps to implement measures to protect the salmon," said David Nicholas, an attorney representing the conservation groups, on Tuesday. "If they don't, we're facing an extinction possibility."

NextEra declined to comment on the lawsuit on Tuesday.

Attorneys or representatives for Miller, Topsham and Brookfield did not immediately respond to requests for comment on Tuesday.

The environmental groups are represented by Joshua R. Kratka and Charles C. Caldart of the National Environmental Law Center and David A. Nicholas and Bruce M. Merrill of Law Offices of Bruce Merrill PA.

Nancy Skancke of Law Offices of GKRSE is representing Miller and Topsham.

Counsel information for the other defendants was not immediately available Tuesday.

The cases are Friends of Merrymeeting Bay and Environment Maine v. Miller Hydro Group, case number 2:11-cv-00036; Friends of Merrymeeting Bay and Environment Maine v. NextEra Energy Resources Inc. et al., case number 2:11-cv-00038; Friends of Merrymeeting Bay and Environment Maine v. Topsham Hydro Partners Limited Partnership, case number 2:11-cv-00037; and Friends of Merrymeeting Bay and Environment Maine v. Brookfield Renewable Power Inc. et al., case number 1:11-cv-00035, all in the U.S. District Court for the District of Maine.

--

Bibeka Shrestha

Reporter

Portfolio Media, Inc.

Publisher of the Law360 Newswire

860 Broadway, 6th Floor

New York, New York 10003

Direct: (646)783-7147

bibeka.shrestha@law360.com

www.law360.com

----

Green Groups Sue Maine Dam Operators Over Salmon

By Bibeka Shrestha

Law360, New York (February 1, 2011) -- Two conservation groups have sued NextEra Energy Resources Inc. and other hydroelectric dam operators on the Kennebec and Androscoggin rivers in Maine, accusing them of harming the endangered Atlantic salmon population by allowing the fish to pass through turbines.

Friends of Merrymeeting Bay and Environment Maine filed four complaints on Monday against NextEra, Brookfield Renewable Power Inc., Topsham Hydro Partners Limited Partnership, Miller Hydro Group, Merimil Limited Partnership and several affiliates in the U.S. District Court for the District of Maine, alleging violations of the Endangered Species Act and the Clean Water Act.

The lawsuits target the owners and operators of four dams on the Kennebec River and three dams on the Androscoggin River, alleging these dams are killing or injuring migrating salmon that try to pass through spinning turbine blades, and are otherwise impeding the salmon's ability to travel upstream and downstream on the rivers.

The dam operators have violated the Endangered Species Act by preventing Atlantic salmon from reaching a significant amount of spawning and rearing habitats and significantly impairing the salmon population's essential behavior patterns, according to the complaint.

Merimil, NextEra, Brookfield and their affiliates are also violating the Clean Water Act by not conducting a required study to prove that allowing downstream-migrating adult salmon to pass through their dams' turbines is safe, the complaint said.

These companies are allegedly violating water quality certifications, which require them to conduct site-specific quantitative studies in consultation with the the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or the National Marine Fisheries Service to show that passage through the turbines does not result in significant injury or death.

Atlantic salmon were officially designated as endangered under the Endangered Species Act in June 2009, the same month the NMFS designated the Kennebec and Androscoggin rivers as critical habitats, according to the complaint.

The rivers, which share a common estuary at Merrymeeting Bay, historically enjoyed the largest Atlantic salmon runs in the country, estimated at more than 100,000 adults annually, according to the groups.

In 2010, however, 10 adult salmon returned to the Androscoggin and five adult salmon returned to the Kennebec, the groups said.

“These dams are pushing an iconic Maine fish to the brink of extinction," said Emily Figdor, director of Environment Maine, in a statement Tuesday. "With the number of Atlantic salmon perilously low, the need for action to protect the fish and their habitat is urgent."

The groups are asking the court to order the dam owners and operators to conduct a biological assessment to determine whether their actions are adversely affecting the salmon population.

They also hope to block the dam owners and operators from allowing salmon to swim through operating turbines unless they receive authorization through an incidental take permit or incidental take statement, which would require them to minimize and mitigate the impacts of harming the endangered fish to the "maximum extent possible," the complaint said.

The groups claim the dam owners can implement simple measures, such as installing effective devices to divert salmon from turbines and stopping the turbines during salmon migration season.

"The salmon population is nearly extinct, and the dam owners and operators need to take immediate steps to implement measures to protect the salmon," said David Nicholas, an attorney representing the conservation groups, on Tuesday. "If they don't, we're facing an extinction possibility."

NextEra declined to comment on the lawsuit on Tuesday.

Attorneys or representatives for Miller, Topsham and Brookfield did not immediately respond to requests for comment on Tuesday.

The environmental groups are represented by Joshua R. Kratka and Charles C. Caldart of the National Environmental Law Center and David A. Nicholas and Bruce M. Merrill of Law Offices of Bruce Merrill PA.

Nancy Skancke of Law Offices of GKRSE is representing Miller and Topsham.

Counsel information for the other defendants was not immediately available Tuesday.

The cases are Friends of Merrymeeting Bay and Environment Maine v. Miller Hydro Group, case number 2:11-cv-00036; Friends of Merrymeeting Bay and Environment Maine v. NextEra Energy Resources Inc. et al., case number 2:11-cv-00038; Friends of Merrymeeting Bay and Environment Maine v. Topsham Hydro Partners Limited Partnership, case number 2:11-cv-00037; and Friends of Merrymeeting Bay and Environment Maine v. Brookfield Renewable Power Inc. et al., case number 1:11-cv-00035, all in the U.S. District Court for the District of Maine.

--

Bibeka Shrestha

Reporter

Portfolio Media, Inc.

Publisher of the Law360 Newswire

860 Broadway, 6th Floor

New York, New York 10003

Direct: (646)783-7147

bibeka.shrestha@law360.com

www.law360.com

Redfin Pickerel in the Brooks of Easton, Mass.

The redfin pickerel (Esox americanus) is the smallest and least known member of the pickerel and pike family, which contains the more well known and much bigger chain pickerel, northern pike and muskellunge. Chain pickerel (Esox niger) and redfin pickerel are the two species of the family native to Massachusetts.

Redfin pickerel are very small, usually less than 5-6 inches, and only rarely up to 10 inches. Since they are quite similar in appearance to chain pickerel, most people who have seen a redfin pickerel assume it is a very small chain pickerel.

Redfin pickerel occupy a fairly unique niche along the Atlantic seaboard: very small first and second order brooks. In some areas, such as northern New England, this niche would be occupied by the brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis). Unlike redfin pickerel, native brook trout are extremely intolerant to water temperatures much above 65 F.

Easton is unusually situated at the very top of the divide between the Neponset and Taunton River watersheds. For this reason, especially in North Easton, most of the brooks are truly first order streams, meaning they rise directly from isolated marshes, bogs, seeps and springs. In contrast, a second order brook is one formed by the joining of two first order brooks. Nearly all of the brooks in Easton are first or second order, meaning they are very small and have a very limited watershed. Brooks of this type have some very unusual attributes, including, unfortunately, that they can periodically dry up during prolonged droughts.

Prior to 1978-1979, an enormous tract of woods existed from Holmes Street and Linden Street in North Easton all the way to Stoughton and the Stoughton Fish and Game club. It was bordered by North Main Street on the west and Washington Street on the east. Around 1979 a large chunk of this land was turned into subdivisions.

Before 1979, however, I used to walk these woods quite a bit. They had all been cleared for pasture in the 1800s as evidenced by stone walls running through the woods this way and that. Just to the west of where Whitman Brook crosses the railroad tracks near the Stoughton line I discovered a tiny brook, barely a foot or two across, that stayed wet all year round, and flowed into Whitman Brook. So one day after school I followed its trace.

At some point a century earlier a farmer had a little cart path that crossed the brook and made a tiny bridge over the brook using some flat pieces of glacial rock nearby. It was quite odd seeing such an old, but obviously handmade little piece of construction way out in the middle of the woods. Leaning on my belly on the piece of granite I looked into the water and was surprised to see a tiny pickerel, no more than 3-4 inches long, hovering in the current like a brook trout, head pointed upstream, waiting for a little insect or other bit of food to float by. I watched him for about a half hour.

Now, in hindsight, I'm quite certain I was watching a redfin pickerel, whose ancestors had probably been living in that little tiny brook for the past 8,000 or so years.

Unfortunately, the little brook was destroyed the next year to build Phase IV of a bunch of McMansions.

Too bad.

Logperch in the Brooks of Easton, Mass.

The Logperch is a member of the darter family of fish (Percina). This family also includes the yellow perch, so common to Easton's ponds and deeper, slower streams.

The darters are an incredibly varied and diverse group of freshwater fish, even though most are just a few inches long. The logperch is the largest of the darters, reaching a length of up to about six inches. Darters are unusual in that most lack swim bladders, have wildly outsized pectoral fins and the males display extraordinarily bright colors during mating season.

On the Atlantic coast, Massachusetts is just about the northern limit of darters, although there exist historic reports of the swamp darter in several brooks in York County in southernmost Maine. Interestingly, darters are quite common in the mountain brooks of central Vermont. Those I used to observe as a kid in East Corinth, VT were probably the Johnny Darter, one of the most common and best known of the family.

My experience with the logperch in Easton is limited to a single observation back in the late 1970s when I was in junior high school. We lived just up the street from Whitman Brook where it crosses Elm Street and goes into Langwater Pond and we used to muck about in the brook all the way to the Stoughton/Easton line.

One summer, most likely in 1977 or 1978, we had a particularly nasty and prolonged drought in and around Easton. Every thunderstorm missed us and you could almost hear the ground groan and sigh for lack of moisture. As my uncle Gilbert Heino would say, it was tough.

One day I walked down Elm Street to Whitman Brook and was shocked to find it was completely dried up just before it enters Langwater. Walking in the brook bed I found dozens and dozens of dead fish, lightly covered with mud. Most were about 4-5 inches long, very slender and kind of odd-looking. Coming back home I figured out, to the best of the descriptions in our various fish books, that they were logperch. Apparently what happened is that the drought was so severe that the logperch got stranded in isolated pools in the brook and when those pools finally dried up, the fish died in them.

What struck me then, and still today, is that we never knew these logperch lived in Whitman Brook. Even with all the fishing and wading and exploring we did in the brook during our growing up years, we never saw them. Apparently, they are quite reclusive little fish. Part of this might be due to our familiarity with the centrarchid family, ie. bluegills, pumpkinseeds and largemouth bass in the local ponds, as well as the chain pickerel. The bass and sunfish family are curiously non-shy, to the point that it almost seems they are as curious about you as you are to them, especially if you are swimming, where the sunfish will come up and nibble at your leg hairs. And underwater, with a diving mask, largemouth and smallmouth bass will swim right up to your face to check you out.

So absent further sightings since 1978, I can only surmise that for all those years of wandering about in Whitman Brook, there were logperch aplenty but they kept themselves extremely well concealed. This is the only logical way to explain how during that one very bad summer drought when Whitman Brook dried up there were dozens of logperch lying dead in the brookbed.

As a side note about our native Percina in Easton, many people are not aware that yellow perch engage in a very interesting spawning migration during April. I first encountered this at the back end of Picker Pond off Canton Street in North Easton. Picker Pond is fed by two brooks, one coming from Flyaway Pond and the other from Long Pond which both meet in a marsh before the pond actually starts.

Walking the little brook from Long Pond one April I was surprised to see fish in it everywhere -- far more than you would ever expect to see in such a small brook. Upon closer inspection I discovered they were all the yellow perch in Picker Pond. They had swam from the pond into the fast water of the brook to mate and lay their eggs. It was quite a sight.

Tuesday, February 01, 2011

The Brooks of Easton, Mass.

This is a short medley of some underwater video I took in 2009 and 2010 in a few of the little headwater brooks in Easton, Massachusetts. Rather than wait for the 'full blown' coverage I'd like to do, this will suffice for now.

The first brook has no formal name. We've always called it, unimaginatively, 'the brook.' It's behind the house where I grew up on Linden Street in North Easton. It actually starts not far from Long Pond and flows east behind Canton Street, then between Linden and Holmes Streets, under the railroad tracks then into the Ames estate where it joins Whitman Brook on Elm Street. All of the video looking up at the trees is actually through the water -- that's how clear the water is.

This brook often dries up in the summer during dry spells, except for isolated pools, so its aquatic population is mostly insects, particularly water striders (Jesus bugs) and the occasional crayfish. This is from July 31, 2010, one of the hottest days of the summer. We had just gotten a big thunderstorm so the brook came up a bit from being almost dry. Since it was so hot I went out back of my mother's house and found this one tiny pool that was about a foot deep and took a dip. The water felt unbelievably good -- it was about 65 degrees probly. And clean !!!

The second brook is actually in East Mansfield. It is a little tributary of the Canoe River that comes into Canoe River campground at the 'tenting site' there. It's really pretty. This is about 200 yards up a red maple kind of swampy thing from the border of the campground. We had gotten a big thunderstorm the night before so the water is a bit turbid. This little brook has native bog iron in its bed.

The third brook is Black Brook at the old railroad grade in the Hockomock Swamp in South Easton. Black Brook is aptly named since unless the water is less than six inches deep it is so colored by tannic acid you can't see the bottom. It's not that the water is muddy or murky -- it's crystal clear -- but it is clear like reddish root beer is clear. The last clip is not underwater, but just looking down at the little pool just above the railroad grade with the reflection of the trees overhead.

The still photo at the end is my brother Tim standing above Queset Brook along Sullivan Ave. where it goes underneath the railroad tracks. This is what William Chaffin called "Trout Hole Brook" in his History of Easton from 1888. It is the one brook in Easton which has good, documented evidence of formerly supporting native brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis). It lost its native brook trout population in the late 1700s when it was dammed up for the Ames Shovel Works, which caused the water to become too warm and polluted to support native brook trout. This section of Queset Brook could support native brook trout again if several of the old dams on it were removed, which they should since they serve no useful purpose except to louse up the brook.

What's interesting is how each brook has a completely different water color. The Linden Street brook is crystal clear; the little Canoe River tributary is cream soda colored and Black Brook is almost ruby red. This is from the varying amounts of tannic acid leaching into the water from decaying leaves.

The music is an excerpt of a little improv song I made up around 1994 on a cheap Casio keyboard. A few months ago I put an electric bass guitar on it which thickens it up a bit. The melody line is a transparent rip-off of the melody line of "Third Stone from the Sun" by Jimi Hendrix with various fake embellishments.

[Note: The compression used by youtube doesn't like underwater video that much; on my computer it looks best at the '360p' setting.]

"No Laughing, No Having Fun" by EZ7.

Even a blind squirrel finds a nut sometimes.

Our song, "No Laughing, No Having Fun," by EZ7. Written by Rick Burns and Greg Hinckley. Recorded live to digital two-track in the Burnsboro Disc Golf pro shop in Vassalboro, Maine, Saturday night, Jan. 15, 2011.

Rick Burns vocals, Mike Fife drums, Pete Burns bongos, Greg Hinckley rhythm guitar, Geoff Hursch wah wah guitar, Mike Southerberg acoustic guitar, Sax Mike on the tenor saxophone, Doug Watts bass and back-up vocals.

Video produced by Doug using footage from the (now demolished) Statler Tissue factory in Augusta, Maine ; the old Cony High School in Augusta; and the Watershed Center for Ceramics in Edgecomb, Maine.

The band's name is a frisbee golf joke for when you throw it into the woods ('that's an easy seven').

The words are about some bitter frisbee golf match between Rick and a guy named Charlie Wilson.

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

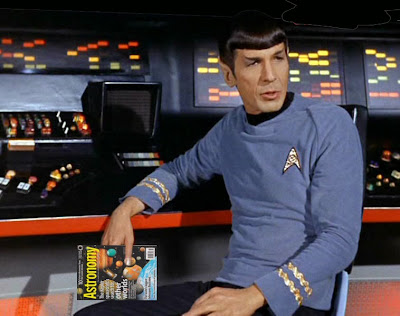

Star Trek: The Big Daddy of Bad Astronomy

By Doug Watts

with apologies to Dr. Phil Plait,

the original Bad Astronomer.

If the Earth was a foot from the Sun the next nearest stars would be 50 miles away.

Space is aptly named.

Watching old Star Trek re-runs my wife reminds me that in the later versions of the series the producers tried to keep the scripts somewhat close to science.

But if this were truly true, you really couldn't have a show. You'd mostly have this:

This is not to knock Star Trek, which has always been one of my favorite TV shows, but is more about having some fun with science.

Star Trek requires that in 200-400 years people in space ships can travel megazillions of times faster than the speed of light. This is illustrated by stars zipping past the ship's view screen as if they were farm houses zipping past as you drive down a highway. This is done, of course, to show us viewers that the ship is moving really fast.

Except in the dense center of our galaxy, the average distance between stars in the Milky Way is around five light years: 30 trillion miles. So we can estimate the average travelling speed of a ship in a typical Star Trek set-up shot as about 5 light years per second, or 30 trillion miles per second. In contrast, light pokes along at a measly 186,000 miles per second.

5 light years per second is 300 light years per minute; 18,000 light years per hour and 432,000 light years per day. This is problematic for a 'sciencey' show set in the Milky Way Galaxy.

The Milky Way is a barred spiral galaxy about 80-100,000 light years in diameter. Its width (from top to bottom) is about 16,000 light years at the central bulge and gets much thinner as you move out from the center bulge.

This means that at the ship speed shown in a typical Star Trek episode, the Enterprise would travel all the way through the Milky Way in about six hours. If the ship was aimed in any direction except parallel to the disk of the galaxy, the ship would be completely out of the Milky Way Galaxy and into the emptiness of intergalactic space in just a couple of hours. The ship would arrive at the Large Magellanic Cloud, our nearest galactic neighbor (160,000 ly), between breakfast and supper and would reach the Andromeda Galaxy (2.5 million ly), our nearest large galactic neighbor, in a week.

Andromeda on 5 Quatloos A Day

In a favorite early episode of mine, the USS Enterprise is hijacked by the deliciously suave and evil Rojan (Warren Stevens) and his friends from the planet Kelvan in the Andromeda Galaxy so they can use the Enterprise to get back home. Because the journey to Andromeda will be so long, they turn the whole Enterprise crew into little styrofoam icosahedrons and soup up the Enterprise so it can go a zillion times faster than normal, which is already a megazillion times faster than the speed of light.

However, even at normal Enterprise speed, Rojan and the Kelvans could get home to the Andromeda Galaxy in a bit more time than it took for Kirk to beat up Rojan and make out with his hot wife Kelinda (Barbara Bouchet), who like, all Kelvans, is actually a 100 tentacled creature.

The Great Energy Barrier at the Edge of the Milky Way

A Star Trek staple is that a giant 'negative' energy barrier surrounds the Milky Way Galaxy that no normal matter, like a space ship, can pass through. This is a critical plot point in the episode with Rojan, Kelinda, Tomar, Hanar and Drea of the Kelvans, since Kirk has the chance to flood the engines of the Enterprise with this negative energy and blow up the ship as they pass through the Great Energy Barrier. But instead, Kirk decides the best way to save the Enterprise is for Scotty and Tomar to get totally shitfaced:

For Spock to whip Rojan's ass at three dimensional chess and for Kirk to get all Barry White with Kelinda and then beat the crap out of Rojan when he gets jealous.

The Great Energy Barrier? It doesn't exist. Even when Gene Roddenberry was first outlining the series, no scientist ever speculated such a Great Energy Barrier existed. He made it all up. But it's still kool.

Star Trek Voyager: Too Fast and Too Slow?

Star Trek: Voyager is a weird cross between Star Trek and Gilligan's Island and Lost in Space but is more ridiculous and contrived than all combined, if that is possible.

When Voyager begins, we are told the ship has been throttled by a weird alien dude into the "Delta Quadrant" of the Milky Way Galaxy, far from the "Alpha Quadrant" where Earth is located and all the other Star Treks are set. Then we are woefully told that even at 'maximum warp speed' it will take 70 years for Voyager to return home to the "Alpha Quadrant."

A quadrant is one fourth of the galaxy, so this means there is a maximum of about 50,000 light years between the outermost edge of the "Delta Quadrant" to the center of the Milky Way Galaxy and into the inner part of the "Alpha Quadrant." This equates to travelling 50,000 light years during 70 years; or a speed of a bit less than 1,000 light years per year of travel which equates to 1,000 times the speed of light.

But even at 'moderate warp speed,' Voyager is shown in typical 'Star Trek' mode whizzing by stars at the rate of a half dozen stars per second. This speed equates to 432,000 light years per day. At this speed, Voyager would get back to the Alpha Quadrant of the Milky Way not in 70 years, not in 7 years, not in 7 months, not in 7 weeks, not in 7 days, but in about 7 hours.

This ship speed, which is zillions of times faster than the speed of light, raises some troubling functional issues. How do you steer that fast? How do you stop? How do you swerve around all those stars? How do you even see the stars?

Deep Space Nine and the Worm Hole

Aside from that it might be the best series of the series, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, uses the premise that a 'worm hole' exists in the 'Alpha Quadrant' that leads directly to the distant 'Gamma Quadrant' of the Milky Way. All types of fun and death then ensues. The problem, again, is that at the speed the Star Trek ships are shown routinely travelling, they could reach the 'Gamma Quadrant' in a few hours without even using the 'worm hole.' Oh well.

Captain, we've a wee bit of a problem.

In 'Star Trek' terms, the speed of light is really slow, like riding a bike with square tires up a steep hill.

Real science is way weirder than even the weirdest science fiction. And it's also real! One of the weirdest parts of science is Special Relativity, which deals when stuff, like us, goes almost as fast as the speed of light.

Swiss Patent Clerk Albert Einstein published his scientific paper on Special Relativity in 1905. The most important 'take home' message of his paper is that nothing can go faster than the speed of light. The only thing that can go as fast as light is light.

Special Relativity is Actually Pretty Simple

Special Relativity does two things to stuff like you and I if we are moving very close to light speed.

1. It makes us more massive.

2. It makes time slow down.

It does other stuff too, like make us shorter in the direction of motion, but we need not deal with that now. These two are plenty weird enough, and have actually been proven in experiments with little tiny itty bitty things like protons and muons, which are the only things we've ever been able to speed up to something approaching the speed of light.

A lot of Special Relativity deals with the weird things that happen to matter as it gets close to the speed of light. And since SR is a set of mathematical equations, we can look at what would happen if a piece of matter actually reached the speed of light.

Well first, it would become infinitely massive, as in it would weigh more than the entire Universe put together. There goes the diet plan !!! [1]

Also, time would stand still, so starting that diet could always wait until tomorrow, since it would never come.

It's a procrastinator's dream come true. With infinite food !

The SR equations dictate that a piece of matter would become infinitely massive if it could reach light speed, and as such, it would take an infinite amount of energy to make it actually reach light speed, so the whole Enterprise would kind of grind to a speedy halt.

But on Star Trek, the entire ship travels not just at the speed of light, but way way way faster than the speed of light. So this is a problem.

The Whole Time Stops Part

Assuming you could get a ship to go at light speed, time would stop. Time wouldn't stop outside the ship, but it would stop inside. At light speed, you would be everywhere at once. You'd be where you were and where you are, all at the same time. Because time stops. The concept is so bizarre that Albert Einstein decided one afternoon that only light can do this or else we would all go insane. [2]

But there's an even bigger problem. To reach the speed of light you first have to reach almost the speed of light, like say .9999999999999 ... the speed of light. At this speed, time seems completely normal inside your ship. However, time everywhere else, including on Earth is moving 99.999999999 ... percent faster than your time. So within a few seconds of travel by your clock, not only is everyone you know on Earth long dead, but the Sun has died out and so have all of the stars you are trying to visit. Long before you get 'there' there is no longer any 'there' to get to.

And this is just at near light speed, never mind zillions of times faster than light speed, like the USS Enterprise.