Striped Bass, Plum Island, Newbury, Massachusetts.

By Douglas Watts

Augusta, Maine

October, 2009

New historic and archaeological evidence shows striped bass migrated much farther up Maine's Kennebec and Penobscot Rivers than previously imagined.

Up until 2000, the "conventional wisdom" of Maine fisheries biologists was that striped bass did not migrate up the Kennebec River past Waterville and Winslow, Maine (20 miles above the head of tide) and did not migrate up the Penobscot River past Indian Island at Old Town (10 miles above the head of tide).

Matt Kay of Augusta, Maine with a striped bass on the Kennebec River in Augusta, Sept. 1996. The Edwards Dam can be seen in the background. It was removed three years later.

Striped Bass from Kennebec River at Pettys Rips, Waterville, Maine, 2004, 15 miles above the site of the Edwards Dam, removed four years earlier. The striper was electrofished and released as part of a biological study (Yoder et al. 2004).

Kennebec and Sebasticook River Striped Bass

The "conventional wisdom" on the Kennebec River was overthrown in 2002 with the discovery of burned, calcined striped bass bones at a 1,000 year old Ceramic Period prehistoric habitation site on the East Branch Sebasticook River in downtown Newport, Maine (Spiess 2003). The striped bass bones were found 50 miles upstream of the confluence of the Sebasticook and Kennebec Rivers at Waterville and Winslow, Maine. This archaeological find shows that prior to 19th century dam building, striped bass seasonally migrated into and inhabited most, if not all, of the Sebasticook River watershed, and were sought and captured as food by the native people who lived in the area 3,000 years ago.

Site of 1,000 year old fishing and habitation site at outlet of Sebasticook Lake, Newport, Maine on East Branch Sebasticook River, May 2004.

Prior to this discovery, the migration limit of striped bass in the Kennebec River was assumed to be near the confluence of the Kennebec and Sebasticook Rivers in Winslow, Maine, based upon historic evidence in Atkins (1869) which stated that prior to dam building, the migration of striped bass was stopped at Ticonic Falls on the Kennebec River in Waterville and striped bass only migrated "a short distance" up the Sebasticook River above its mouth.

Red arrow at Waterville shows previously assumed upstream limit of striped bass in Kennebec River. Red arrow at Sebasticook Lake in Newport shows additional migration area based on striper bones found in 2002 at Ceramic Period habitation site at outlet of Sebasticook Lake.

The earliest version of Charles Atkins' Fishery Commissioner Reports to the Maine Legislature (Atkins 1867) states that, prior to damming, striped bass went "some distance" up the Sebasticook River. It is not known why Atkins in 1869 changed the language of his 1867 report ("some distance" up the Sebasticook) to the more narrow and conservative phrase, "a short distance" up the Sebasticook.

Charles Atkins' first Maine Fish Commissioners Report in 1867 regarding striped bass shows he got it right in his first report and got it wrong in his later reports. Atkins' reference to winter fishing in the Eastern River in Dresden, Maine (an estuarine tributary of the lower Kennebec River) gives a rather strong clue as to why striped bass had become extremely scarce by the time of his writing. These folks in Dresden were wiping out the entire population of native, sexually mature striped bass overwintering beneath the ice in the lower Kennebec River. Once they caught them all, there were none left to spawn the next spring. Oops.

The construction of the Edwards Dam on the Kennebec River at its head of tide in Augusta, Maine in 1837 ended all migrations of striped bass, Atlantic salmon, American shad, alewives and other fish species up the Kennebec River. For this reason, Charles Atkins was forced to rely upon interviews and recollections of elderly people in the Kennebec River valley to reconstruct the geographic range and migrational extent of striped bass and other fish in the Kennebec River. Atkins himself had never seen the Kennebec River in its natural, undammed character.

Tim Watts with a large striped bass from the Kennebec River at Hallowell, Maine, June 1997. This is a joke photo since we saw the striper floating dead on the river and I convinced Tim to hold it up as if he had caught it.

The archaeological evidence gathered by Spiess (2003) doubles the known, historic migrational range of striped bass in the Kennebec River system, from approx. 50 miles above saltwater to more than 100 miles above saltwater. This discovery also calls into question many of the "conventional wisdoms" held by fisheries biologists regarding the extent to which striped bass utilized freshwater habitat in large coastal river systems. One of these conventional wisdoms is that striped bass tend to confine themselves to the large, deep portions of rivers near and below the head of tide even in the absence of natural migration barriers.

Blue line shows previously assumed historic range of striped bass in Kennebec River system. Red line shows additional range based on archaeological evidence from Sebasticook Lake in Newport.

The Penobscot River Striped Bass

An eyewitness account from 1825 describes very large striped bass in the Piscataquis River, 20 miles above Old Town. This account is taken from early 19th century Bangor newspaper articles summarized in Godfrey (1882). The articles describe a massive forest fire in August of 1825 that burned the lower Piscataquis River valley and the Penobscot River valley from Mattanawcook to Passadumkeag. It states:

"1825: For a fortnight fires were raging in the forests north of Bangor. At one time nearly the whole country from Passadumkeag to Mattanawcook, on both sides of the Penobscot and Piscataquis, was a sea of flame. The roaring of the fire was like thunder, and was heard at a distance from twelve to fifteen miles. The islands in the river were burnt over. The country between Passadumkeag and Lincoln was devastated. The towns upon the Piscataquis suffered from loss of buildings, cattle, fences, crops. The house, barn filled with hay, and store and toolhouse of Joseph McIntosh, of Maxfield, were burned and the family driven to the river for safety. Other houses and barns, and saw-mills and grist-mills, were destroyed. A lad returning from school through the woods was so badly burned that his life was despaired of; hawks and other birds were killed by the fire; and the fish in the Piscataquis River were killed by the heat. Twenty bass, weighing from twenty to forty pounds, many young salmon, shad, trout, and other small fish, were found dead in the shoal water and on the shores."

Red arrow at Old Town shows previously assumed upstream migration limit of striped bass in Penobscot River system. Red arrow in upper left shows the area of the intense forest fire in 1825 in which large striped bass were found dead in the Piscataquis River.

Eyewitness documentation of very large striped bass in the Piscataquis River in 1825 has profound significance for our understanding of the natural ecology of the Penobscot River marine-riverine ecosystem. The gentle gradient and lack of any steep falls on the mainstem Penobscot above Indian Island means striped bass had access to the entire Penobscot River mainstem, the lower reaches of the East and West Branches of the Penobscot in Medway and East Millinocket, and the Piscataquis, Passadumkeag and Mattawamkeag watersheds below their first major falls. All of these waters supported large alewife, blueback herring and shad populations which would give the striped bass an incentive to follow the runs upriver in spring and remain to feed on spawned out adults and down-migrating juveniles in the midsummer, late summer and fall. The name "Shad Pond" given to the lower West Branch Penobscot in Medway shows that the lower West Branch would have attracted feeding stripers during the entire summer and fall. The very large historic American eel population throughout the entire Penobscot drainage would give yet another incentive for striped bass to remain in the middle and upper Penobscot mainstem for significant portions of the year.

Blue line shows previously assumed historic range of striped bass in Penobscot River, based on belief that striped bass were blocked by rapids in Old Town. Red line shows historic range based on 1825 documentation of striped bass in the Piscataquis River, 20 miles above Old Town.

Danny Watts with a striped bass from the Weweantic River, Buzzards Bay, Cape Cod, 2007. This striper is of the size documented in 1825 on the Piscataquis River (20-40 lbs.). Stripers of this size are sexually mature females.

The size of the dead striped bass observed in the Piscataquis River in 1825 (up to 40 lbs.) shows the species was the apex predator and largest fish to inhabit the Penobscot River above Indian Island in Old Town.

The Two Imperatives of Striped Bass in Freshwater

Striped bass have two motivations to migrate up large coastal rivers into freshwater riverine habitat: feeding and spawning. Feeding forays into freshwater are spurred by the seasonal migrations of alosids (alewives, blueback herring and American shad) and American eel, all of which cohabit these waters with striped bass and prior to 19th dam-building, existed in very large numbers in the Kennebec and Penobscot river systems. Spawning is the second motivation. Striped bass spawn in freshwater and must deposit their eggs well above the freshwater/saltwater interface for them to survive. This is because striped bass are "broadcast spawners" and deposit their eggs in mid-river in June and early July. The eggs have neutral buoyancy and drift downstream with the current for 24 hours or more before they hatch. If the eggs drift into saline water (in excess of 1 ppt) before they hatch, they die. For this reason, sexually mature striped bass must migrate a considerable distance above the freshwater/saltwater interface in order to spawn successfully. Scientific papers supporting the above are as follows:

Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (1995) states: "Historically, striped bass probably spawned in all larger rivers along the Atlantic Coast prior to the construction of dams and deterioration of water quality (ASMFC 1990). For many stocks, spawning areas are fresh to brackish waters and are generally located in the first 25 miles of freshwater in the river, with salinities of 0-5 parts per thousand. Some fish, such as those in the Hudson, Rappahannock, Roanoke and Neuse Rivers, migrate over a hundred miles upstream from the river mouths to spawn (Janicki et al. 1985)."

Dadswell (1996) states: "Striped bass are large, percoid fish which can attain lengths of 150 cm and weights of 40-50 kg (Scott and Scott 1988). Spawning is estuarine and freshwater usually near the head of tide in water of less than 1 part per thousand salinity (ppt; Setzler-Hamilton et al. 1981), but in some rivers as far as 120 miles upstream of tidewater (Roanoke River, N.C.; Rulifson and Mannoch 1990)."

Squiers (1988) states: "The spawning areas [of striped bass] range from head of tide in Chesapeake Bay to small tidal river systems 12 miles upstream to 80 miles above tidewater on the Roanoke River in North Carolina and 200 miles above tidewater on the St. John River in Canada. The location of spawning is probably an adaptation of certain stocks to the water temperatures at the time of spawning. Upriver spawners are probably early run fish while tidal river spawners would probably be late run spawners in order for egg incubation to coincide with availability of freshwater flow. This would allow for adequate incubation time before the fry reach low salinity waters. Studies by Rathjen and Miller (1955) demonstrated that live striped bass eggs in the Hudson River were not found in areas of salinity in excess of 1: 1,000. Therefore, upriver and near head-of-tide stocks of striped bass have to be very temperature sensitive in order to accommodate egg incubation time with extent of freshwater flow."

Scott and Crossman (1973) noted the presence of spawning striped bass in the St. Lawrence River as far upstream as Montreal: "Throughout its range the striped bass spawns in fresh water. In the St. Lawrence River there is a fall migration upriver, the potential spawners spend the winter in the river, then swim up to their spawning grounds in the spring, usually spawning in June. Prespawning fish may travel long distances upriver, in fresh water. In former years some large fish have been taken as far inland as lac Saint-Pierre and a very few individuals have been caught at lac Saint-Louis in Montreal ... In some rivers spawning occurs just above the head of tide, but in most cases the ripe fish seem to move well into fresh water before spawning."

The above citations clearly show that striped bass in many river systems select spawning habitat many miles above the head of tide; and that this adaptive behavior ensures spawning success by preventing striped bass eggs from reaching saline waters prior to hatching. The mainstem Penobscot River above Old Town is situated well within the range of spawning migrations observed for striped bass in large rivers in the eastern United States. The 1825 account describing large stripers in the Piscataquis River forces us to re-examine the conventional wisdom that the Penobscot River did not support a spawning population of striped bass. This account shows that striped bass of spawning size migrated 40-60 miles above the summer salt wedge on the Penobscot River. This is the same distance above saltwater influence that striped bass now travel on the Kennebec River (Bath to Waterville, approx. 60 miles) . Just like at the Kennebec River at Waterville, the mainstem of the Penobscot below Medway, Mattawamkeag and Howland is more than sufficient to allow striped bass eggs to incubate and hatch before reaching saline waters in the lower Penobscot River.

Are Striped Bass "weak" swimmers?

A common "conventional wisdom" against extensive freshwater migration by striped bass in Maine rivers is that they cannot negotiate large, steep ledge drops and falls on rivers, and for this reason were stopped by the first significant falls on a coastal river. This failure is variously attributed to striped bass being "weak" swimmers that cannot swim through heavy water and the inability of striped bass to leap clear out of the water, like Atlantic salmon, to pass over a falls. While it is true that striped bass do not leap straight out of the water like Atlantic salmon at falls, it is completely untrue that they are "weak" swimmers and cannot swim in currents easily negotiated by alewives, blueback herring and American shad. This is demonstrated by striped bass at the large tidal rips at Woods Hole, Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

Striped bass caught by Tim Watts off Nauset Light, Woods Hole, Cape Cod.

The Woods Hole Tidal Rips

Woods Hole gets its name by being a "hole" in the Elizabeth Islands, which separate Buzzards Bay from Vineyard Sound on the south side of Cape Cod. Because several hours separate the timing of high tide between Buzzards Bay and Vineyard Sound, twice a day an enormous tidal rip occurs in Woods Hole as water flows from Buzzards Bay (when it is at high tide) to Vineyard Sound (when it is below high tide) and vice versa. Because Woods Hole is shallow, these tidal rips create very strong currents and large standing waves (similar to Class IV whitewater) where the current breaks over submarine boulder piles and ridges. Large striped bass use these "rips" as feeding stations for bait fish swept through the channel at Woods Hole and can be caught in large numbers, even though the current is so swift that maintaining a boat in them is dangerous.

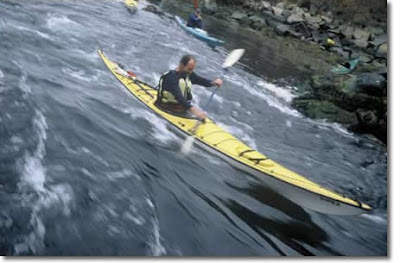

Kayaker and writer Dave Jacques describes kayaking the Woods Hole tidal rips in a 2005 article in Wavelength magazine:

"Woods Hole, like nearby Robinsons and Quicks Holes, is a narrow gap in the Elizabeth Islands through which tides pour daily, year in, year out. The tides run in concert with the phases of the moon and are so consistent that their patterns can be accurately detailed for years to come ... We paddle out into the Woods Hole channel with a hard lean and strong ruddering, and the kayaks slide into the heavy, 5-knot current. Surfing the standing waves produced by the current, we ferry out into the middle of Woods Hole. We look down and see the current is ripping along under us over rocky shoals covered with colorful seaweed and kelp. A striped bass shoots by. Rather than being swept backward by the current, however, we find ourselves surfing forward. We are riding the standing waves, letting them do the work."

U.S. Coast Guard charts show maximum tidal flow in Woods Hole Passage is about five knots. This is a current velocity of 8.4 feet per second. We know by direct evidence that large striped bass are extremely numerous in the rips at Woods Hole feeding during maximum tidal flow, which means they are inhabiting an area with a steady current of 8 feet per second. While stripers take advantage of velocity refugia behind boulders in this area, they frequently go straight into the main current itself to chase bait fish being blown through the passage. This figure of 8 feet per second is considered by U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to be the maximum current velocity for upstream migrating fish (USFWS 2009).

Striped bass in the rips at Woods Hole passage are not trying to move through this heavy current to get upstream, but are selecting and sitting in these currents, day in and day out, eating smaller fish. This shows that rapids and tidal bores with a current velocity of 8 feet per second are often a preferred living habitat for large striped bass, not a "difficult spot" they would prefer to avoid, but must somehow pass through, in order to get upriver. It is hard to imagine how, among sea-run fish, striped bass could ever be called "weak" swimmers since of all sea-run fish, striped bass are the only ones which seek out and inhabit areas of extreme current for feeding and living purposes. Yet the "conventional wisdom" decrees this.

Yearling (9 inch long) native striped bass. Caught by Doug Watts at Negwamkeag, Kennebec River, Sidney, Maine in July, 2000, one year after the Edwards Dam was removed in Augusta in 1999. Negwamkeag is a Kennebec/Abenaki word which refers to large gravel bar islands.

The Problem with "Conventional Wisdoms"

The problem with "conventional wisdoms" in the natural sciences, in this case fisheries science, is they are often based on a lack of evidence and for this reason, are often profoundly wrong. On the Kennebec, modern fisheries biologists have relied exclusively on Charles Atkins' brief, anecdotal statements from the 1860s about the upstream migration limit of striped bass in the Kennebec River system. Because the Kennebec had been impassable to fish above its head of tide in Augusta since 1837, Atkins was forced in 1867 to rely solely on the recollections of "old timers" to gain any information on how far striped bass actually went up the Kennebec and Sebasticook Rivers before they were dammed. Newly acquired direct evidence, in the form of striped bass bones found on the Sebasticook River 50 miles above Winslow, Maine shows Charles Atkins' estimates of striped bass range in the Kennebec were wrong. We now know the range of striped bass in the Kennebec River system is twice as large as Atkins had estimated.

On the Penobscot River, Atkins said little about striped bass. Lacking any historic evidence, modern fisheries biologists themselves erected an arbitrary migration limit on striped bass at the rapids and ledges at Indian Island in Old Town. At this writing, the State of Maine Dept. of Marine Resources is uncertain if it will "allow" native striped bass to move up the Penobscot River past the Milford Dam in Old Town once access is made available with the pending removal of the two mainstem dams below it. This is based on the "conventional wisdom" that striped bass never swam past the Milford Dam site, in spite of direct historical evidence from 1825 which shows they did.

Danny Watts of North Easton, Mass. with a striped bass from the Kennebec River at Bacons Rips, five miles above Augusta, Maine. July, 2003.

David Watts of North Easton, Mass. (Danny's great uncle) and a friend with two striped bass caught on Cape Cod in the 1950s.

References Cited:

Atkins, C. 1867. Maine Fish Commissioners Report in Twelfth Annual Report of the Secretary of the Maine Board of Agriculture. Stevens & Sayward. Augusta, Maine.

Atkins, C. 1869. Report of the Maine Commissioners of Fisheries. Augusta, Maine.

Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. 1995. Amendment No. 5 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Atlantic Striped Bass. Fisheries Management Report No. 24 to the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. Washington, D.C.

Baxter, James P., editor. 1910. Documentary History of the State of Maine Containing the Baxter Manuscripts. Vols. 1-24. Maine Historical Society. Lefavor-Tower Company. Portland, Maine.

Buck, Rufus. History of the Settlement of Bucksport: 1763 to 1860. Unpublished, handwritten manuscript in Maine historical documents collection at Maine State Library, Augusta, Maine. Rufus Buck born in 1797, died in 1879. Manuscript written in 1860s era.

Dadswell, M.J. 1996. The Removal of Edwards Dam, Kennebec River, Maine. Its Effect on the Restoration of Anadromous Fishes. Prepared for the Kennebec Coalition. Augusta, Maine. March, 1996.

Godfrey, J.E. 1882. The Annals of Bangor, 1769-1882, in History of Penobscot County, Maine. Williams, Chase & Co. Cleveland, Ohio.

Jacques, D. 2005. "Playing in Woods Hole." Wavelength magazine. Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada. (pdf here).

Maine Dept. of Marine Resources. 2008. Strategic Restoration Plan for the Penobscot River. Maine Department of Marine Resources. Augusta, Maine.

Scott, W.B., E.J. Crossman. 1973. Freshwater Fishes of Canada. Bulletin 184. Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Ottawa, Canada.

Spiess, A. 2003. Newport Stream Restoration Archaeology Survey and Site 71.30. Maine Historical Preservation Commission. Augusta, Maine. (pdf here.)

Squiers, T. 1988. Anadromous Fisheries in the Kennebec River Estuary. Maine Department of Marine Resources. Augusta, Maine.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. 2009. Letter of Andrew Raddant, Regional Environmental Officer, to Federal Energy Regulatory Commission on Application of Surrender for Great Works, Veazie and Howland Dam, Penobscot and Piscataquis Rivers, Sept. 2, 2009. USFWS, Boston, Mass.

Watts, D. 2003. Native and Commercial Fisheries of the Penobscot River. Prepared for the Penobscot River Restoration Trust. Augusta, Maine.

Yoder, C., J. Audet, B. Kulik. 2004. Maine Rivers Fish Assemblage Assessment: Interim Report. Midwest Biodiversity Institute. Columbus, Ohio.

Allan E. Watts of North Easton, Mass. night fishing for striped bass in the salt marshes of Haskell's Island, Aucoot Cove, Buzzards Bay, Mattapoisett, Mass. July, 1993.

1 comment:

palm angels t shirt

golden goose outlet

birkin bags

jordan 11

off white

supreme official

supreme new york

bape shoes

bape

palm angels hoodie

Post a Comment